“You’re a dope if you don’t steal from everybody you’ve ever worked with.”

– Tom Hanks

Chris Fenton, the agent turned author of “Feeding the Dragon, Inside the Trillion Dollar Dilemma facing Hollywood, the NBA and American Business,” apparently has no problem with that sort of theft. And while those might be wise words for actors, I don’t think he was talking about Hollywood agents.

For many people in the industry like myself, the intrigue of working with China is prevalent. The future of the film industry is a Silk Road that links these countries and economies. Yet, there are very few people that have mastered the art of the deal between these widely disparate cultures. I was hoping this book would unlock the mysteries surrounding how to break into and master this lucrative market.

Through the first few chapters of this book, I thought maybe Mr. Fenton held the keys to the kingdom.

But the deeper I got into “Dragon,” the more things did not add up. Over the next few days, reality kicked in and I started pondering things that no longer make sense.

Is Mr. Fenton the all-knowing seer he claims to be? Or just a guy out to make a buck, portraying his limited exposure to the art of deal-making as actual expertise?

One of the reasons I was interested in this book is that Mr. Fenton had been doing the media rounds on several shows such as Steve Bannon’s (whom he considers a friend) War Room Pandemic, Tucker Carlson and The Epoch Times. Interestingly, Bannon, President Trump’s former chief strategist, was arrested back in August and given a trial date of May 24, 2021.

Bannon, 66, was arrested on his luxury yacht for allegedly siphoning money from We Build the Wall, an online fundraiser for Trump’s contentious border wall with Mexico. Federal prosecutors allege that Bannon used a non-profit he controlled to divert “over $1M from…the online campaign, at least some of which he used to cover hundreds of thousands of dollars in personal expenses,” according to The Guardian.

Scandals aside, the one thing these venues have in common is that they have a need to create news segments that are topical. When China is on the hook, they bite, craving content.

Mr. Fenton presented himself on these outlets as an authority on doing business in China. But did anyone fact check “Feeding the Dragon?” I did, and it wasn’t that hard.

I reached out to several individuals and organizations mentioned in Mr. Fenton’s book, seeking clarification. Those replies led to me asking questions that helped fill the gaps in what Mr. Fenton presents.

The former agent worked at William Morris Agency (WMA), MBST, DMG, and IDW, per his memoir. In reading, chatting with former colleagues, and good ‘ole fashioned research, I discovered he was fired from the first three, while his year-long consulting contract at IDW was not renewed.

DMG is currently embroiled in a lawsuit with Mr. Fenton: According to court documents and sources at Variety, the lawsuit claims Mr. Fenton engaged in “poor performance, gross mismanagement, and fraud.”

This publicity has allowed Mr. Fenton to spin a narrative that may be convincing to someone on the outside looking in but also enables him to blow a lot of smoke throughout U.S. and China’s entertainment industry without any fire.

Back in August, I requested an interview with Mr. Fenton to discuss his new book. We talked about his background as an agent, and now an author. Throughout our conversation, it seemed that he continued to position himself as an expert, perhaps, even looking for a consulting gig on anything and everything China-related.

In “Dragon,” Mr. Fenton states that his “adopted country” is China. Most would infer he spent time there; quality time that’s paramount if the goal is acquiring working expertise in the field.

In doing my research, I was surprised to learn from a former DMG employee that Mr. Fenton was only in China a handful of times. In reality, he didn’t directly work on any of the productions mentioned in the book. My sources also indicated that he did not work on the marketing or distribution either.

In fact, they described Mr. Fenton to me as someone who “was really more of a handler for some talent that came through.” He outright says so at the beginning of his book, where he talks about working with Robert Downey Jr’s security detail. Not the grandiose dealmaker I would’ve hoped to read about.

As the book continues, Mr. Fenton elucidates his transition from the service industry to the entertainment industry. His journey began as the “Robin Hood” of Olive Garden, stealing food but only for himself, and moving on to his “historic first-time licensing agreement between the U.S. and China.” Crediting this agreement as the inspiration behind “Chris Fenton’s Five Forces,” his edicts of building bi-lateral relationships as if he wasn’t primping enough, he goes on to confess that World War Z would have been better with his ending. Those were only a few of the cringe-worthy moments in the book.

During our interview, I presumed “you must speak Chinese?” His reply? “No, I don’t.” After reading the book and his media coverage, I felt that was a safe assumption to make. It made me wonder further how he became associated with that market. This led to the discovery of DMG and the lawsuit.

The more I learned, the more intrigued I was about how Mr. Fenton became associated with DMG. By his own admission, Mr. Fenton was fired from William Morris, he stated that he was just “too nice of a guy.” Look, if you’re going to spill the beans (even selectively) in a memoir, at least give us enough information so that we aren’t left scratching our heads. But, that piece of information was “coincidentally” left out of his book. I wonder what else was left out.

After more digging, I discovered that Mr. Fenton also worked at MBST, a prestigious management company at the time, for over a year. One would think this would’ve garnered at least a chapter.

I reached out to Andrew Tenenbaum, CEO at Creative Management & Productions and a former talent manager at MBST, which represented the likes of Billy Crystal, Woody Allen, and the late Robin Williams.

Tenenbaum acknowledged that Mr. Fenton was in fact employed by MBST for a few years and that some “bad shit went down.” And he was fired for cause.

Additionally, the former DMG employee told me that Mr. Fenton was not only fired from MBST but was locked out of their offices. The source then confided that the firing was due to attempted theft of clients and intellectual property.

In my continued efforts in understanding this timeline, I asked more questions.

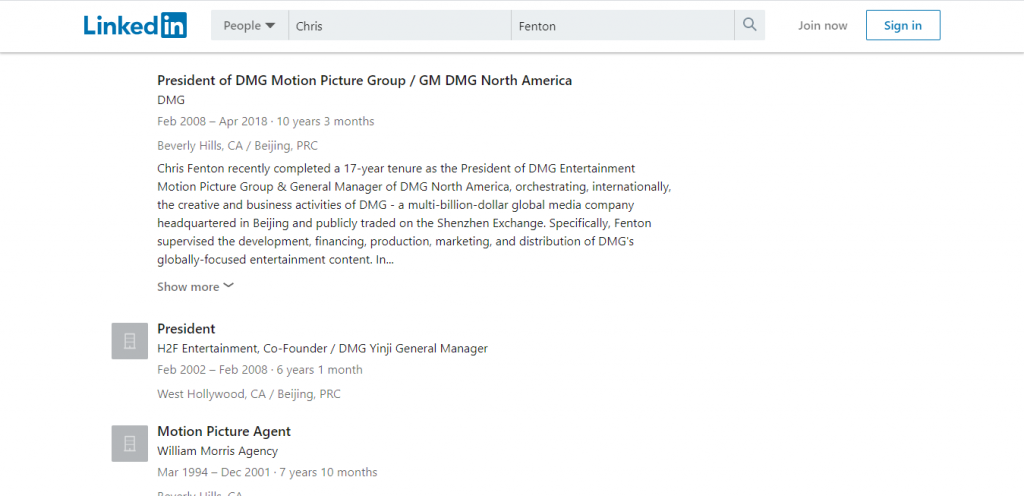

I began with Mr. Fenton’s resume as “president” of DMG for 17 years, at least that’s what his memoir says and subsequent interviews he has given.

His LinkedIn says the timeline was much shorter, displaying a 10-year tenure at DMG from February 2008 – April 2018, as shown below:

But I discovered that Mr. Fenton was a DMG employee for only five years. Exaggeration is a polite term for that sort of misrepresentation. But why was he given this title as “President?” The former DMG employee also told me that Mr. Fenton requested a title like that because it might help him open more doors for the company.

However, it appears he only used it to open more doors for himself.

In the end, this left me with a bigger question: why write a narrative that seems to be exceptionally tailored to misleading readers?

Having traveled to Hong Kong, Beijing, Shanghai, and other parts of China ten years ago on a study abroad program, I had the most difficult of times simply asking for bathrooms. We literally “Pictionary-ed” our way around if we couldn’t grasp the pronunciation.

This is why I was hoping to read a book that would illuminate the complex worlds of deal-making and filmmaking in China in today’s digital age.

But how much of an expert can you be if you don’t speak the language or spend any real time there?

Why claim that you’re an expert when you’re not?

Perhaps, it has something to do with the pending lawsuit that a former employer has against you? Or, is it a positive spin on a career punctuated with bad exits from WMA, MBST, and DMG? Not an impressive resume.

From reading the book, interviewing the author, and doing my homework, I realized that Mr. Fenton doesn’t hold the secret of how to make successful deals in China. Being someone who is close to the deal-making, yet not a part of it doesn’t qualify you as an expert.

Maybe that is why Mr. Fenton’s true expertise is: being lucky enough to find himself in close proximity to the real dealmakers, which he refers to as his “Rolodex” system.

I don’t think Tom Hanks meant for individuals in the industry to literally steal insights from the best in the business, claiming it as their own. Unfortunately, that’s why the film industry dislikes people like Mr. Fenton because he perpetuates the image of the Hollywood agent as being disingenuous.

Sure, Mr. Fenton knows just enough to present certain facts about China and the film industry’s work there. But can he discuss these topics with any legitimate authority? My research leads me to believe that no, he cannot.

When it comes to “Feeding the Dragon,” Mr. Fenton may have been invited to lunch, but he wasn’t the one actually making or serving the meal.